Creative work should be fresh but also familiar. Raymond Loewy’s Maya theory explains why.

The Account Planning Group’s inspirational Creative Strategy Awards closed for entries this week. At the risk of imperilling 101’s entries, and at odds with the prevailing awards tide, I hope the venerable judges find time to salute those strategies that demonstrate caution as well as creative daring.

It’s a contrary position to take with regard to an awards scheme now dedicated to transformational thinking, I’ll grant you, so let me explain.

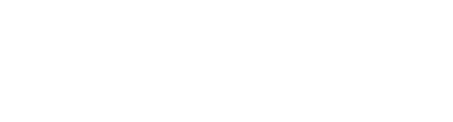

When Raymond Loewy first proposed his masterful Maya theory, he wrote the playbook for advertising planners – not just industrial designers.

Great design solutions, Loewy figured, played to two competing human impulses – our interest in the new and our deep-seated comfort with the familiar. The designer’s goal, therefore, was to find the “most advanced yet acceptable” answer to his or her brief. Excite and assure in equal measure.

Far from being a charter for mediocrity, Maya explains not only many of Loewy’s groundbreaking designs but also why some new brands and businesses disrupt successfully while others fail – the new rides in undetected on the coat-tails of the old. (Steve Jobs’ artful introduction of the iPhone once we had become familiar with the iPod is a case in point.)

Loewy’s theory receives a timely reboot in Derek Thompson’s new book Hit Makers: the Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction. (Required reading for all, except perhaps Ed Sheeran.) And although I suspect few marketers and ad people are taught the principles of MAYA, let alone go about our business with it uppermost in our minds, I believe much of the best brand thinking and many of the best advertising solutions conform to this blueprint.

They honour current beliefs while remaining determined to stretch or at least update them. The best communication starts with listening, after all. And it is agency planners, the reluctant stars of the APG’s show, who may be best-placed to “keep the flame” in their myriad roles of brand guardian, “chief engineer” and occasional change agent.

At risk of caricature, creative folk will tend to strike out for the most advanced solution, then bewail the failure of others to either “get it” or buy it. It’s in their nature and it’s what our rewards system drives them towards – the dopamine rush of a bauble. (Creative awards skew towards the new.)

A few – it’s true – instinctively wear a MAYA hat, whether that is to guide them to the right ideas or simply to stuff that gets made. And unfashionable as creative teams now may be, they would often have a built-in “auto-correct” – one partner reaching for the stars, the other with feet planted firmly on the ground. One live wire, one earth.

For the mortal creative, however, the planner – and strategy more generally – can be their friend in two regards – helping them get straight to “most advanced” answers that are intrinsically acceptable (to the consumer, remember, not necessarily the brand owner) and/or policing the unacceptable. My personal preference is for the former.

A good brief and a good briefing is still a great place to start in the quest for surprising advertising that is accepted rather than rejected, even if the APG Awards raised its gaze beyond this many moons ago. The best briefs steer everyone to what Loewy called “optimal newness” – answers that are at once fresh but somehow familiar, original and appropriate. (“Draw me the court I’m playing on and I’ll try to hit the line,” my creative partner, Augusto Sola, says.)

However, once creatives are up and running, the planner’s task is to act as a kind of clutch control: a role that demands a light touch and a gift for nurture (of ideas, that is – not necessarily people), because creative people need to feel they got there themselves and, of course, often do. And because no-one likes a smart-arse.

Just as it does in the spheres of music and film, our industry’s most popular output works because we recognise something familiar even as we embrace the new. Look more closely and our most transformational thinking may actually be grounded in acceptability, not just the more obvious “advance”.

So as the APG judges gather to celebrate the new, they are reminded of an old truth. Here’s to the less crazy ones.